Dennis D. Weisenburger, known as Denny to friends and colleagues, is a leading hematopathologist in the US. Originally from North Dakota, he spent most of his career at the University of Nebraska in Omaha, where he remains active as Professor Emeritus in Hematopathology. He has made major contributions to lymphoma research, co-founding, with James Armitage, the Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group – a key resource for lymphoma studies worldwide.

Weisenburger also played a major role in the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project and helped lead large international studies, such as the International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project and the Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Study. These efforts helped define the clinical and pathologic features of several types of lymphomas globally. He held many leadership roles and trained over 100 hematopathology fellows, including around 50 from other countries.

Ivan Damjanov sat down with Weisenburger to learn more about his exemplary career in hematopathology and continued support to projects and leadership initiatives.

Where did your interest in hematopathology blossom?

While I was studying pathology at the University of Iowa, I became especially interested in both renal pathology and hematopathology. Unsure which to pursue, I applied to top fellowship programs in both fields. I was first accepted into the renal pathology program at Harvard under Ramzi Cotran and Emile Unanue, and shortly thereafter I was offered a hematopathology fellowship at City of Hope under Henry Rappaport, which I accepted.

Excited by the rapid advancements in cellular immunology at the time, I chose hematopathology as the more dynamic research path – and continued in the field for the next 45 years. Most of my career was spent leading the hematopathology division at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

In 2012, I returned to City of Hope as Chair of the Pathology Department, where I rebuilt the team with a focus on hematopathology and molecular genetics to strengthen its already excellent clinical hematology and bone marrow transplant programs. I retired in 2021 and moved back to Nebraska to be near my family and grandchildren. Today, I remain active as an emeritus professor at the University of Nebraska, mentoring young pathologists in research and diagnostics.

How did you establish yourself as a hematopathologist, given that there were no subspecialty Boards in hematopathology when you were training?

In the early days, pathologists became subspecialists mainly through hands-on experience and later through fellowship training. I was fortunate to do both, though I never took the hematopathology Board exam because my academic and personal life became too busy. Still, I later contributed by writing questions for the exam.

I was drawn to hematopathology because I enjoyed the work and had strong, rewarding relationships with hematologists during my internship and residency – connections that lasted throughout my career. Although I also started out in surgical pathology and cytology, I was encouraged early on to focus on hematopathology, which became my main specialty.

You joined the Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group (NLSG) at the University of Nebraska in 1984. Can you tell us a little bit about the inspiration for the NLSG and its importance for both your career and the field of hematopathology?

The NLSG was conceived and started by James Armitage, Chair of the Department of Internal Medicine, and David Purtilo, Chair of the Department of Pathology at the University of Nebraska School of Medicine in Omaha. This took place a few years before I joined the team. I played an important role in organizing the pathology reviews for the cases registered by the NLSG and began collecting fresh, fixed, and frozen tissue samples from each patient for diagnosis and research.

The NLSG was created to support high-quality clinical and translational research in lymphoma and related blood cancers. We also provided pathology services across Nebraska and nearby states, allowing many patients to receive treatment in our protocols while staying in their local communities. Our registry included detailed clinical data and follow-up for each patient, including pathology diagnoses, immunologic markers, and genetic findings. This allowed us to conduct clinicopathologic, translational, and basic research at a time when such work was just beginning in clinical medicine, and helped us set a standard for other institutions.

In 2012 you became the Chair of the Pathology Department at the City of Hope, the very department where you started your hematopathology career. What did it mean to you to come full circle in your career?

My two periods at the City of Hope were very different, but both were rewarding. I first trained with some of the top hematopathologists of the time, and later returned to lead the department and help train the next generation. I also built a world-class molecular diagnostics lab to support research on blood cancers and solid tumors.

You are one of the few pathologists in the US (and beyond) who was able to successfully combine demanding leadership roles, busy and complex clinical service, teaching, and exceptionally prolific research. Are these different aspects complementary and how do you do it all?

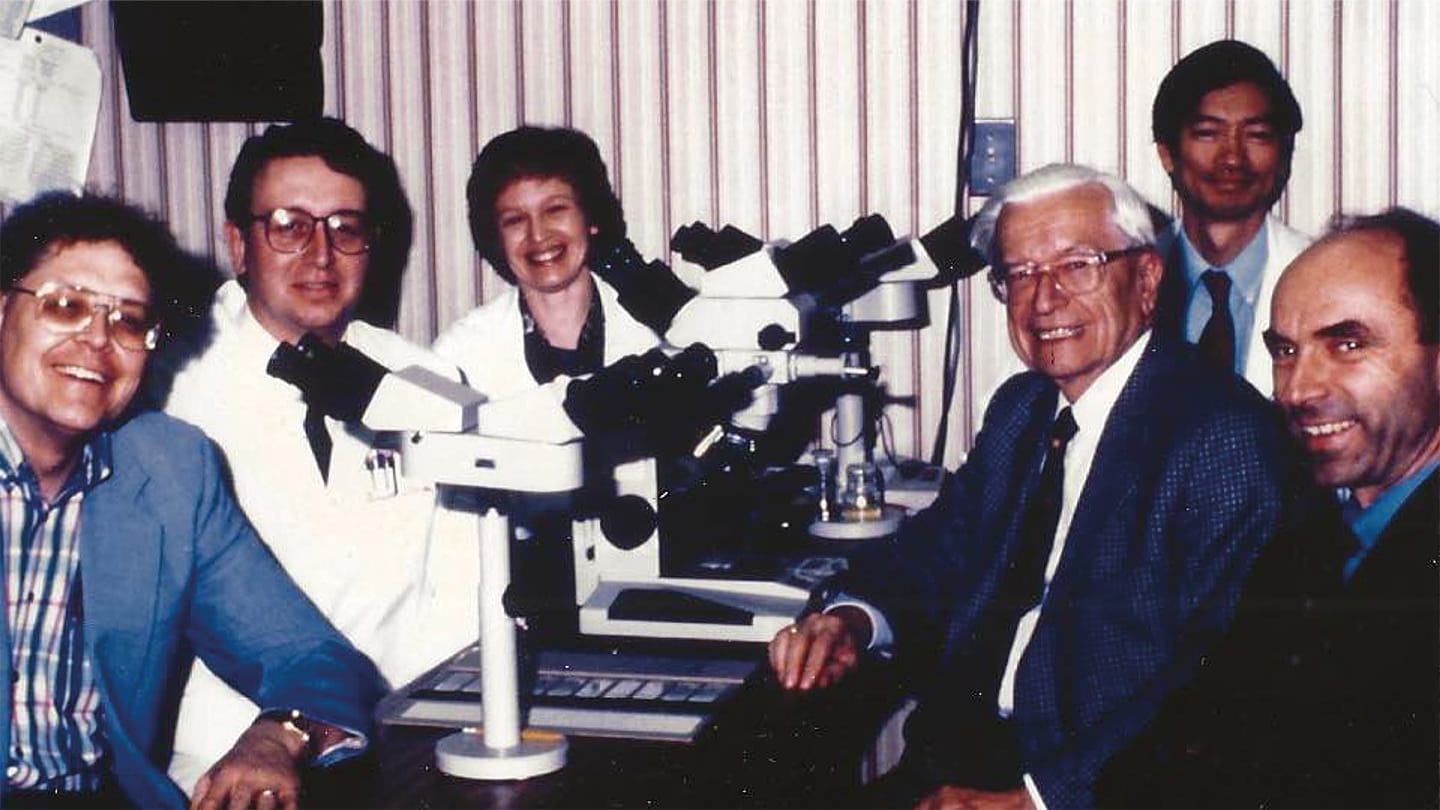

Yes, all of these activities go hand in hand in academic practice. I was able to bring together a talented team of junior and senior hematopathologists – including John Chan, Timothy Greiner, Samuel Pirruccello, Patricia Aoun, Kai Fu, and Joo Song – to help carry out our work. Our strong program also attracted many excellent fellows and research trainees, all of whom were expected to contribute to research alongside clinical duties and teaching. We collaborated closely with a great group of cytogeneticists led by Warren Sanger and an exceptional team of hematologists led by James Armitage and Julie Vose. Together, we had the people, tools, and resources needed to do important research at the time.

Can you tell us about some of what you believe are your most impactful contributions to the biology and prognostic markers of various lymphomas?

As a hematopathology fellow, I wrote two early papers on mantle cell lymphoma. The first showed that the disease had poor survival and was not curable, which challenged the belief at the time that it was an indolent disease. The second paper described an early pattern of infiltration in some cases, suggesting that the disease starts in the mantle zones of lymphoid follicles.

At Nebraska, we continued publishing on mantle cell lymphoma, including studies showing that P53 mutations worsened outcomes in both mantle cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. We were also among the first to use paraffin-based antibodies like CD43 (L60) and CD20 (L26) to help diagnose lymphoma.

When the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification was introduced in 1994, it sparked a lot of debate. In response, James Armitage and I organized the International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. We recruited collaborators from around the world who provided cases with both pathology slides and clinical data. A team of five expert pathologists – including Jacques Diebold, Konrad Mȕller-Hermelink, Kenneth MacLennan, Bharat Nathwani, and myself – traveled internationally to review and diagnose the cases. This project produced multiple papers confirming the value and reliability of the new classification system, highlighted how lymphoma subtypes varied by region, and identified nodal marginal zone lymphoma as a distinct disease. It also laid the foundation for the 2008 World Health Organization Classification.

In 2000, we partnered with Stanford University and the National Institutes of Health to use gene expression profiling to identify two biologically distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), each with different survival outcomes. This was possible thanks to Nebraska’s large frozen and paraffin tissue bank. That collaboration led to the creation of the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project (LLMPP), a 20-year international effort involving pathologists, clinicians, and scientists. The LLMPP produced many influential papers on the biology of lymphoma, confirmed the unique features of the GCB and ABC subtypes of DLBCL, described primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, discovered cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma, and identified new types of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The group also pioneered research on how the tumor microenvironment affects lymphoma progression.

During this time, James Armitage, Julie Vose, and I also launched the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Study to better understand this rare and complex group of lymphomas. We followed a similar model: global collaboration, expert pathology reviews, and international site visits. This work led to key discoveries, including the recognition of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma as a separate disease. We also gave lectures and seminars during these visits. Since then, research into peripheral T-cell lymphomas has continued in the labs of John Chan at City of Hope and Javeed Iqbal, his former trainee at Nebraska, with the goal of finding better treatments for these difficult to treat cancers.

You are well known for your work in the field of lymphoma epidemiology – what are your most important discoveries in this area?

When I moved to Nebraska in 1984, local clinicians mentioned the unusually high rate of lymphoma in Eastern Nebraska. I suspected it might be linked to farming practices, as farmers are known to be at higher risk. I conducted an ecological study and found that lymphoma rates were significantly higher in areas with heavy agrichemical use. With support from the Nebraska Health Department, I launched a large case-control study in partnership with Aaron Blair and Shelia Hoar-Zahm from the National Cancer Institute. Later, I worked with Brian Chiu on another study that examined the role of diet and lifestyle in lymphoma risk.

We found that certain pesticides – both insecticides and herbicides – raised the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) in farmers. Drinking groundwater contaminated with pesticides and nitrates from fertilizers also increased risk. Among women, using dark, permanent hair dyes was another risk factor. Diet played a role too: eating a lot of red meat and fat increased the risk, while eating more citrus fruits and leafy greens reduced it.

In 2001, this work led me to help organize the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph), a global group of experts dedicated to understanding lymphoma causes. I chaired its Pathology Working Group for 14 years. The group pooled data from many studies and found several important risk factors for NHL, including immune system disorders, autoimmune diseases, obesity, chemical exposures (like pesticides and organic solvents), hepatitis C, and family history of blood cancers. On the other hand, moderate alcohol use and regular physical activity were linked to lower risk.

We also analyzed risk factors by lymphoma subtype and published our findings in a special issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2014. In addition, the group studied genetic risk, identifying gene variants that increase susceptibility to lymphoma.

My background in pathology and epidemiology also led me to serve as an expert consultant in legal cases involving exposure to chemicals like organic solvents and glyphosate (Roundup) – both linked to NHL – and asbestos, which is not linked to lymphoma.

As an experienced educator, what are your views on hematopathology training?

I have trained over 50 hematopathology fellows and about 50 international fellows from around the world. The international fellows stayed with us for anywhere from 3 months to 2 years, while the US-accredited fellowship always lasted 2 years. I believe all hematopathology fellowships should be at least 2 years long, because the amount of knowledge and skill required has grown significantly over the past 20 years and continues to increase. A one-year program simply isn’t enough to gain the level of competence needed today. Fellows must now be able to diagnose cases by combining clinical information with results from immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular biology.

Can you tell us about some of the mentors that inspired you through your career?

During my pathology residency at Iowa, Charles Platz and Fred Dee sparked my interest in hematopathology. At the City of Hope, my main mentors were Henry Rappaport, Hun Kim, and Bharat Nathwani. They taught me diagnostic techniques and how to apply new technologies in diagnosing and researching blood disorders. At Nebraska, David Purtilo, my first department chair, strongly supported my clinical and research efforts. The four expert hematopathologists I worked with on international lymphoma studies also taught me a great deal – and became close friends.

Would you recommend hematopathology as a career to medical students?

Yes, hematopathology has a bright future, and I strongly recommend it to students and residents looking for a meaningful and rewarding career in either academic medicine or private practice. The cases are challenging, and the classifications keep evolving as we learn more about these diseases. Fellows need to learn how to make accurate diagnoses and how to use new tools like molecular genetics and artificial intelligence.

Do you think hematopathology will survive the onslaught of molecular biology?

Hematopathology will continue to thrive, even with the rise of molecular biology and other new technologies, which for now are additions – not replacements. While that could change in the future, traditional pathology remains the gold standard for evaluating these new tools. Strong diagnostic skills are still the foundation. That said, we all need to become "hybrid" pathologists who understand and apply new technologies in both practice and research. Some programs now combine hematopathology and molecular pathology into 2- or 3-year training tracks to support this integration.

Though you retired, you continue to work part time as a consultant hematopathologist at the University of Nebraska – what motivates you to keep working?

I enjoy working part time and spending time with the young hematopathology staff, fellows, and residents at Nebraska. I still love pathology, especially solving challenging cases and teaching my approach, as well as mentoring others on research projects. I also continue to enjoy my work as a legal consultant. Outside of work, I like reading a variety of books and journals, keeping up with politics and current events, watching sports, and spending time with my wife and our four granddaughters.

Speaking of sports, I hear you’re a good basketball player – did you learn anything from your time on the court that helped through your hematology career?

Yes, I played both basketball and baseball competitively through high school and continued for enjoyment in the following years. These sports showed me that practice and hard work lead to success, and that healthy competition can motivate you in your career. They also taught me how important teamwork is for the group to succeed.

Any advice for our younger colleagues?

Choose a subspecialty you truly enjoy and find ways to build a rewarding career from it. There’s no substitute for hard work and focused study to become a good pathologist. I learned the most when I did research and wrote papers on a topic, and I strongly recommend this approach to anyone who wants to become an expert in a pathology field.